Voodoo Village; Or Freemasons run the country

Seriously, dudes, don't get out of the car!

I've mentioned before how much I love lurking on Craigslist's Memphis page — especially the rants and raves — because the crap most people post is so unbelievably silly and pathetic and offensive. Never could I have imagined actually learning about something intensely weird and interesting among the scattered swatches of racist meandering and pointless bitching.

Apparently, there's a place in Memphis, steeped in lore and legend, called Voodoo Village.

According to the Craigslist posting, Voodoo Village "(as it's called by white people) is on a one block long road off Shelby Drive just west of Third (past Weaver). The turn takes you north. The road is Mary Angela and there is some sort of church there with all kinds of cool totem looking stuff around."

There's an urban legend (about which a previous poster had inquired) that says if you drive down that street, which is a dead end, the villagers will pull a big schoolbus across the opening of the street, blocking you in, so they can kidnap you and your curious carmates and perform all sorts of ghastly voodoo rituals on you.

While I couldn't find any documentation about that, I did find a few sites that explain the basic legend.

From Haunted America Tours:

Many old time residents avow that the Village is inhabited by a mixed race African-American/Native American tribe led by a charismatic Chief named Wash Harris. It is said that the Voodoo Village tribe practices strange rituals that look and sound a lot like African voodoo, but have all the formality and strangeness of the Freemason rituals of Europe.

Several people have claimed to have witnessed residents of the Village sacrificing animals in these rituals – especially goats and dogs – and for a time there was a vigilante force in southwest Memphis solely to protect the pets of local residents.

Strange artwork and sculptures on the lawns of residents in Voodoo Village only lent to the widespread belief that something “weird” was definitely going on. Sculptures and carvings depicting strange planetary motifs and decorated with symbols that appear to be Arabic or Hebrew can be found everywhere throughout the village. Most are attested to be the work of Wash Harris himself, and he in fact took credit for most of the artwork in rare interviews he granted in the 1980’s.

Since that time there has been little contact with any resident of Voodoo Village and Harris, who would be well over a hundred now, has never spoken to the media again.

The fact that Harris is still called “Chief” by many of the residents and the fact that many believe him to be a saint or immortal has led to speculations that Harris is still alive inside the Village, being closely guarded by his followers.

Though reporters are often chased away, photographers have often felt the wrath of the Villagers and it is a long standing warning that no photographs are to be taken inside the Village or even from the road. Many who have tried have been pelted with rocks and sticks and chased out of the road by machete-wielding residents.

Some locals in the know claim that photographs are prohibited because, once developed, they will reveal the ghosts of the many people who have lost their lives to Villagers over the years. Still others insist that photographs will reveal the Villagers as they truly are — aging and corpse-like, kept artificially young by the many sacrifices and the pacts with the Devil made by their leader, Harris.

For Memphis natives growing up in the area, Voodoo Village was a place of curiosity and fear.

“Everyone got dared to go down there,” says Holly, a native of Memphis now living in Louisiana. “If you were a teenager, it was the thing to do — get chased by the Voodoo people.”

Holly stated that she can remember vividly the fantastic artwork and trees hung with fetishes and spirit bottles, before she and her friends were chased out of the Village by a group of turban-wearing women.

That's it. Brandon, this will be your initiation into Memphis life. I'll drive and you'll very discreetly take photos from the passenger window. Phil will hide in the back seat in case we are confronted by machete-wielding voodoo psychos, at which time he will pop up and use his lethal-weapon karate skills. Or we'll just drive away screaming. That works, too (unless we get blocked in!).

But wait, there's more.

Much of the myth centers on Wash Harris who gave his village the name “St. Peter’s Spiritual Temple” in the 1960’s and claims to be doing the “Lord’s work” there. Reports from those who had access to Harris and his compound at that time say that there is anything BUT a religious feeling back there and that it is more like getting lost in the dark practices of the Congo. Harris’ temple was, they said, decorated with hundreds of tiny fetish dolls and other images syncretized with more familiar religions. Some claim it is clearly a form of Haitian Voodoo.

Others who claim to have lost pets to the Villagers who then used the hapless animals in their strange rituals say that the place should be torn down and the ground burned. They point to the high number of deformities and unusual illnesses in the community surrounding the Village, and they lay the blame squarely on the Voodoo going on there.

This urban legend has quite a historical following.

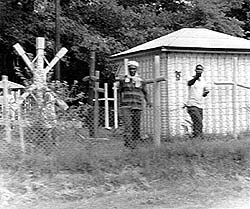

The guys over at The Basement Diaries have documented their early 1970s trip to Voodoo Village here. They even have photos of the place, and, as we've learned, taking photos is a serious risk in Voodoo Village.

I drove past a couple of small houses with what appeared to be some really interesting lawn art. I don't know how many photographs Charlie took as we drove past because I was eager to get turned around.

I turned the car around in a cul-de-sac a the end of the road and headed back the way we had come. Off to the left, from the houses we'd just past, a couple of young men appeared to be coming out to the street to meet us.

As I drew even with the houses, one man had come into the street and was gesturing for us to stop. Which would have been the normal thing to do with someone standing in the middle of the street. But somehow I never considered stopping. Not for a second. In fact, I put it to the floor. And never swerved. The fellow got out of the way and I must have been doing 50 by the time we pulled back onto the highway.

It's impossible to tell from the photograph above so you'll just have to take my word for it. The gentleman in the stripped shirt is holding what appeared to be a machete, down behind his right leg. He probably wanted to sell it to us as a souvenir. Or maybe he wanted to hack on a bunch of nosey white kids with no respect for other people's religion or privacy. And who could blame him.

The Basement Diaries also has a link to a page where they've archived some of the local media's coverage of the village.

July 1961, from the Memphis Press-Scimitar

"We have an eternal organization here. A church. Our temple is the most beautiful place in the world. All these things have a meaning. They are symbols of God."

A canvas awning was pulled back, and he motioned into the temple. The floor, walls, and ceiling were covered with colorful pieces of satin. The little building was filled with other symbols and dolls, illuminated by tiny electric lights.

"It took me four years to make this. Sometimes I would go in in the morning and not come out until the next. How did I do it? By the power of God."

July 1984, from The Commercial Appeal

"Don’t come too close, don’t stop too long and don’t take no pictures," a reporter was told as he parked his car outside the village. Inside the fence are several houses; a homemade temple decorated with crosses, hearts and sunbursts; a half-dozen cars; and countless pieces of handicraft that look like something that might be found in the Twilight Zone between Alice’s Wonderland and the Wizard’s of Oz.

At first glance, much of it looks like the exaggerated objects in a children’s playground –a candle 8 feet tall, a set of wheels connected by a crosscut saw, a giant figure with outstretched arms, fans, spindles, spinners, all in rainbow colors—but the mood is serious rather whimsical.

"All this that you see is my craft," he said. "It is the work of one man, and don’t nobody know what it means but me. People are always coming here trying to me to talk about it, but I don’t discuss it with anyone. If I give it away (the secret, he means) what have I got?"

There’s one gizmo with a propeller big enough to take off and another that looks like a Thunderbird with a pair of horns. There are painted stumps and towering crosses. There are things that make your head real to look at them.

"I’m the only one who understands it," he said. "God told the black man and the Indian some thing he didn’t tell nobody else. The only way you’re ever going to find out what all this means is to get like me."

October 1989, from the Memphis Flyer

As we cruised by the first time, entering seemed unlikely. The entire site is surrounded by a metal fence and the main driveway is blocked by a heavy iron gate. When we returned just minutes later, however, the gate was flung wide open. I parked the car, facing the main road (having been warned not go get trapped in the dead-end street), and we quietly slipped inside the compound, wondering how many eyes might be watching. We marveled at the rough craftsmanship and artistic intricacy of the displays, which looked like products of a whittling disciple of Salvador Dali.

Hearing voices in the shack behind me, I apprehensively mounted the steps. After several knocks, a woman in a white tunic and head-wrapping cracked the door.

"You didn’t take any pictures, did you?" she asked. I had the impression that several people were moving around behind her in the darkened room.

I asked if I could talk to whoever was in charge, but she said I should go away, that maybe I could talk to someone later. I suspected this was just get the gate closed behind us again. As we walked toward the gate, a wrecker backed down the gravel driveway and blocked our path. A man wearing a gas station uniform hopped out, smoking a stubby cigar.

"Did you take any pictures?" he demanded.

I told him we were simply interested in the purpose of the commune and in the art work.

"Are you in a lodge?" he asked, referring to what I assumed had to be the Masonic organization (Wash Harris was reportedly a member of the Masonic Lodge for many years). When I told him I wasn’t, he replied, "Then you can’t understand."

The man identified himself as James Harris, 40, son of Wash Harris. "What’s the name you heard for this place?" he blurted at me. When I said "Voodoo Village," he blurted back, "That’s the name the peckerwoods gave it."

Okay, so after reading all of that, it sounds to me like this eccentric artist/preacher dude, living in a depressed but tight-knit community, went a little nuts with his lawn displays and scared the bejesus out of the white folks in the rest of Memphis, who decided that those black folks must be doing voodoo. As the rumor spread and white teenagers kept driving up and down the street, gawking at the neighborhood, making its inhabitants uncomfortable, the community members decided it would be best to preserve their dignity and the integrity of what their community leader had created by scaring people off and discouraging them from taking photos like it was some sort of circus freak show. This, evidently, involved machetes and an entire city getting on board with the idea that the area was spooky, and while this entire story smacks of racism, it's still pretty creepy if any or all of it is true.

I'm just going to have to drive down there and see for myself.

3 Comments:

Please, this is America. Our national passtime is driving around looking at people who are different than us--the Amish, victims of Hurricane Katrina, etc. Who in this country is left alone? We gawk and stare at each other all the time. It's just our way. So, clearly, the patriotic thing to do is to go and see.

But you might want to stop over at Eebo's or Schwab's first and get you some uncrossing powder.

The way I figure it is, I'm still a tourist here. I drive around and gawk at all sorts of shit — rich white folks' mansions on Belvedere, the constant walkers along Monroe, the cool kids on Cooper-Young — just to drink it all in so I can become better acquainted with this place I'm supposed to call my home.

If I hear about some voodoo shit with crazy lawn ornaments and machete-wielding residents, don't I have a duty to check it out for myself? Or should I just believe all the hype I've been reading and spread it over the internet like some digital venereal disease? Or should I dismiss it as hooey? How can I do either unless I see for myself?

I'll go, and I'll report back, and if you guys don't hear from me, you know what happened.

Brandon, when we capture their corpse souls with that big camera, what will we do with them? Dump them off President's Island like everything else?

OK, forgive my morbid curiosity. Sure, any kind of curiosity is inherently nosy. But you can't say I lack a conscience or empathy just because my interest has been picqued by this local cultural anomaly.

Isn't it condescending and unfair to think of this place as being like Fallujah or an accident scene? I doubt the place is in that much of a bad way. I mean, Fallujah has bombs and snipers and, you know, a real war going on. This little neighborhood just has some cool lawn art that's gained some notoriety and an accompanying legend, and I don't see how it makes me a bad/crazy/empathy-less person to just want to drive by and see the big gate at the foot of the street to know that it's real. Or am I supposed to trust the rumors?

I don't think anything is owed to me, and I don't see how bringing this up and saying I might drive by implies that I think anything is owed to me. I will probably never actually go down there. You see, I talk about a lot of stuff that interests me and then I don't actually do it because I am lazy and scared and I get discouraged.

I just think it's an interesting urban legend that I wanted to share with my non-Memphis readers. It's a story that has persisted through the years because it's creepy and interesting. I'll try to do better to squash my interest in Memphis and its silly myths from now on if they're all so apparently offensive.

Post a Comment

<< Home